On Principles 18 & 19

Summer with Charlotte: The Reason Issue

This is my seventh article in my “Summer Autumn with Charlotte” series. If you missed the first few, you can read On Education, On Principles 1, 2 & 20, On Principles 3 & 4, On Principles 5, 6, 7 & 8, On Principles 9 & 10 , and On Principles 16 & 17.

Let’s get started.

Principle 18 & 19: The Way of the Reason

We should teach children, also, not to lean (too confidently) unto their own understanding because the function of reason is to give logical demonstration of (a) mathematical truth and (b) of initial ideas accepted by the will. In the former case reason is, perhaps, an infallible guide but in the latter is not always a safe one, for whether the initial idea be right or wrong reason will confirm it by irrefragable proofs.

Therefore children should be taught as they become mature enough to understand such teaching that the chief responsibility; which rests upon them as persons is the acceptance or rejection of ideas presented to them. To help them in this choice we should afford them principles of conduct and a wide range of fitting knowledge.

Reference: Volume 6, Chapter 9

If there is one principle that could have a ripple impact on our current culture, I think it’s this one. Understanding the importance as well as the place of reason is crucial and I think it’s a gift we can give our kids, especially in their teen years.

Logic is woefully missing from many teens’ educations and yet our culture leans in unhealthy dependence — and even outright absolute belief — on reason. In a day where science is king and if it can’t be proved it doesn’t exist, how are we to think about reason?

The first thing is to put reason in its place as a wonderful helper but a miserable master. Much like habit, reason can be put to good use and should be but to depend on it as a source of truth is to misstep. Reason can talk us into anything we already believe.

Charlotte gives a compelling example: “How else should it happen that there is no single point upon which two persons may reason, — food, dress, games, education, politics, religion, — but the two may take opposite sides, and each will bring forward infallible proofs which must convince the other were it not that he too is already convinced by stronger proofs to strengthen his own argument.”

Reason is an exercise of the will but the will, as we saw last time, must be governed by truth and virtue. Without these filters in place, we can simply reason our way to what we already desire. If our desires are impure, reason will not hold us accountable; that is the job of will. Once we have pushed the desire on to reason; the end justifies the means.

Charlotte points us to the classic example of Macbeth: “When we first meet with Macbeth he is rich in honors, troops of friends, the generous confidence of his king. The change is sudden and complete, and, we may believe, reason justified him at every point. But reason did not begin it. The will played upon by ambition had already admitted the notion of towering greatness or ever the ‘weird Sisters’ gave shape to his desire. Had it not been for this countenance afforded by the will, the forecasts of fate would have influenced his conduct no more than they did that of Banquo.”

Of course reason itself is not to blame; as Charlotte says, “But it must not be supposed that reason is malign, the furtherer of ill counsels only.” Of course reason can be — and should be — used for good. It is an amazing gift to have the use of reason; humans have accomplished innumerable achievements that have blessed others and reason was required for every invention and innovation. It is a muscle we should all strive to work regularly.

Charlotte explains, “There is no object in use, great or small, upon which some man’s reason has not worked exhaustively. A sofa, a chest of drawers, a ship, a box of toy soldiers, have all been thought out step by step, and the inventor has not only considered the pros but has so far overcome the cons that his invention is there, ready for use; and only here and there does anyone take the trouble to consider how the useful, or, perhaps, beautiful article came into existence.”

So if we utilize reason as a tool instead of a qualifier, we’ll be in good shape. We can keep reason in its place by remembering that we can use it to talk ourselves into anything. If that’s the case, let’s condition ourselves to reason for the good. Charlotte encourages us that “Children should know that such things are before them also; that whenever they want to do wrong capital reason for doing the wrong thing will occur to them. But happily, when they want to do right no less cogent reasons for right doing will appear.”

Reason is a tool at our disposal. She goes on that “…children may readily be brought to the conclusions that reasonable and right are not synonymous terms; that reason is their servant, not their ruler, — one of those servants which help Mansoul in the governance of his kingdom.”

Ah — “reasonable and right are not synonymous terms.” What a good reminder. “Right” brings us back to will - choosing the good thing, but Virtue is where we find what the good thing is. Truth is the absolute authority - what is the Standard? What is required of us? Who decides this? What is right, what is wrong? And yet we can know right and do it for the wrong reason. So we step back once more and find ourselves standing on the love of God as our only pure motive. “If you love me, you will keep my commandments,” Jesus said (John 14:15) and He went on to promise us a Helper, knowing we could not love Him perfectly on our own.

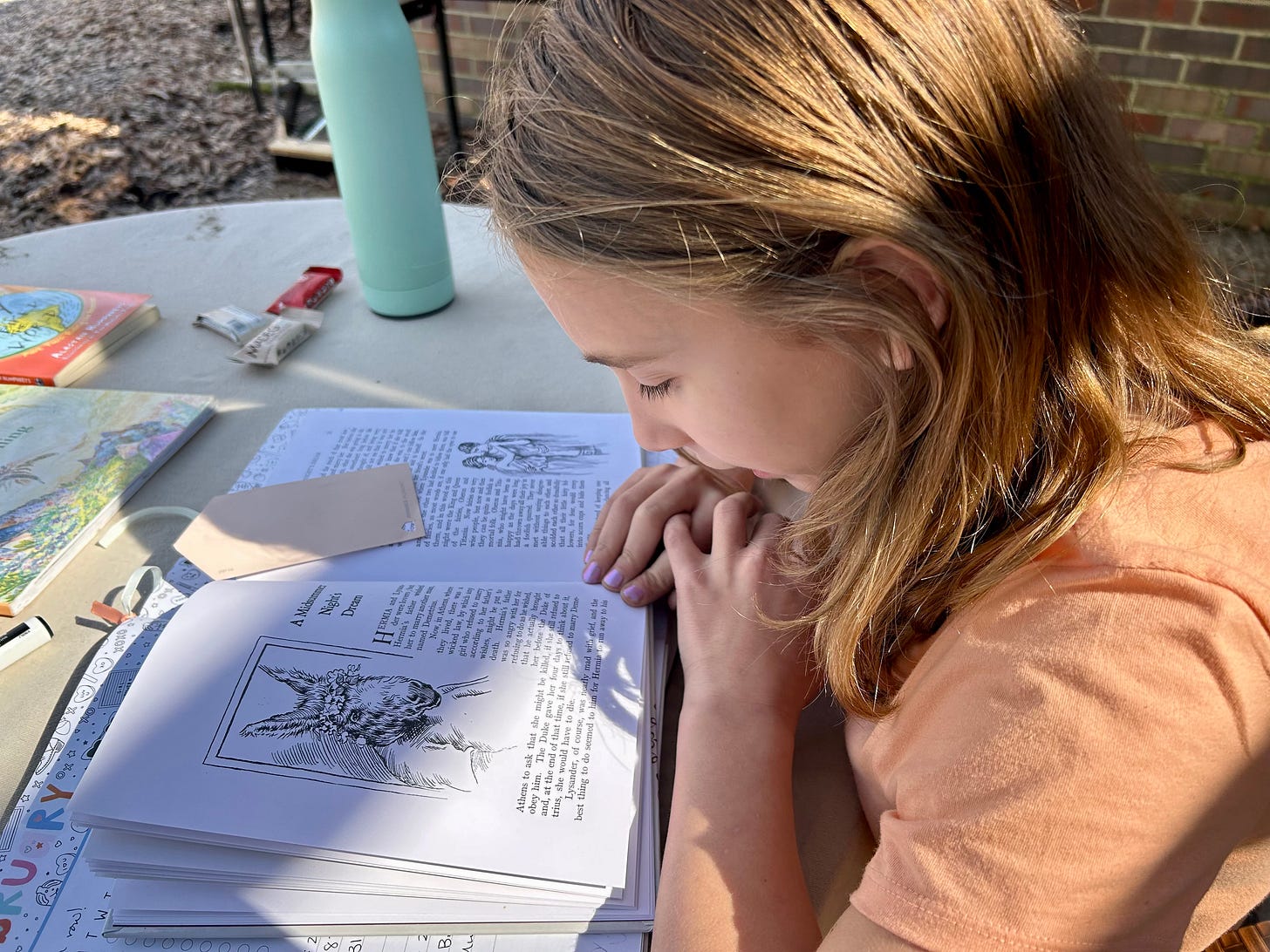

To know what is good and pure and lovely and to be surrounded by it constantly is crucial because only then can we identify with startling awareness what is not. And evil, as we know, is master of trickery. As mothers and educators one of the best things we can do is be the “gatekeeper to our children’s hearts,” as Sally Clarkson says, and flood our children with what is good.

Charlotte remind us, “For ourselves and our children it is enough to know that reason will put a good face on any matter we propose; and, that we can prove ourselves to be in the right is no justification for there is absolutely no theory we may receive, no action we may contemplate, which our reason will not affirm.”

Character is required to use reason responsibly; this is why so much of Charlotte’s emphasis is on the building of the person and not just the teaching of skills. My favorite Charlotte Mason quote appears in this chapter to solidify this point: “But the function of education is not to give technical skill but to develop a person; the more of a person, the better the work of whatever kind;” A person who is honest, loyal, and hard-working can easily be taught many things but no matter how skillful a man is, if he is dishonest, disloyal, and lazy, are his talents really worthwhile?

Education must affect the whole person; to lean too heavily on any academic discipline in the foundational years is a mistake. Reason can be developed and exercised when studying many subjects. Charlotte explains “But they must follow arguments and detect fallacies for themselves. Reason like the other powers of the mind, requires material to work upon whether embalmed in history and literature, or afloat with the news of a strike or uprising. It is madness to let children face a debatable world with only, say, a mathematical preparation. If our business were to train their power of reasoning, such a training would no doubt be of service; but the power is there already, and only wants material to work upon.”

And yet Charlotte urges us not to waste time contemplating every proposition we encounter; some things we must simply accept. “A proposition is idle when it rests on nothing and leads to nothing. Again, blasphemy is a sin, the sin of being imprudent towards Almighty God, Whom we all know, without any telling, and know Him to be fearful, wonderful, loving, just and good, as certainly as we know that the sun shines or the wind blows…I want, am made for and must have a God.”

In the end, being feeble humans we must acknowledge that we cannot reason and explain everything. As Christians we are not called to check our brains at the door but we are asked to accept extraordinary ideas; miracles may not be considered “reasonable” by many people but that does not mean they are not true.

We can still use reason to help us grapple with the unexplainable but in the end we find there are some things in this world we simply cannot prove, which is why faith is required.

Charlotte says, “Children must know that we cannot prove any of the great things of life, not even that we ourselves live; but we must rely upon that which we know without demonstration. We know, too, and this other certainty must be pressed home to them, that reason, so far from being infallible, is most exceedingly fallible, persuadable, open to influence on this side and that; but is all the same a faithful servant, able to prove whatsoever notion is received by the will.”

We live in a world that — 100 years later —is even more enamored with needing proof for everything. The High King Reason is the governing force and ultimate authority of our culture but, no. No, there are things that cannot be explained and that is the magic and beauty of a life of faith.

In a world that values reason over all it’s no surprise that the subjects most associated with reason are held in the highest esteem. In Charlotte’s day, just like our own, there was a push towards overemphasis on math as a study to teach reason.

“We find that, while children are tiresome in arguing about trifling things, often for the mere pleasure of emplying their reasoning power, a great many of them are averse to those studies which should, we suppose, give free play to a power that is in them, even if they do not strengthen and develop this power. Yet few children take pleasure in Grammar…Arithmetic, again, mathematics, appeal only to a small percentage of a class or school, and for the rest, however intelligent, its problems are baffling to the end, though they may take delight in reasoning out problems of life in literature or history.”

We see that although math is a fantastic way to exercise reasoning, it is not the only way. The ability can be practiced with many subjects of study.

“Therefore perhaps the business of teachers is to open as many doors as possible in the belief that Mathematics is one out of many studies which make for education, a study by no means accessible to everyone. Therefore it should not monopolise undue time, nor should persons be hindered from useful careers by the fact that they show no great proficiency in studies which are in favor with examiners, no doubt, because solutions are final, and work can be adjudged without the tiresome hesitancy and fear of being unjust which beset the examiners’ path in other studies.”

And just to drive the point home, Charlotte ends with this:

“We would send forth children informed by “the reason firm, the temperate will, endurance, foresight, strength and skill,” but we must add resolution to our good intentions and may not expect to produce a reasonable should of fine polish from the steady friction, say, of mathematical studies only.”

Although the STEM schools would like to have us think Math and Science are the only subjects that matter to humanity anymore — or at very least they are the most important subjects in this post-modern, tech-savvy world — it seems that we still need to be well-rounded and that even those of us who struggle in those subjects can make valuable contributions to society and become reasonable people.

I can’t resist exposing my inner romantic here by quoting Robin Williams in Dead Poet’s Society: “We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

Yes, our world has changed significantly since Charlotte’s day but no matter how much importance the internet and machines hold in our lives, humanity will always matter more. And it takes all kinds to make this world go round.

A wide, varied curriculum. Cultivating the whole child. Personhood. Education is an atmosphere, a discipline, a life. These phrases all come to mind and I want to scream from the mountaintops to our continually floundering education system that the answer is not more narrow, focused studies. It is to zoom out. It is to consider the whole; to not lose the forest for the trees.

And what should we teach, then? I can’t wait to jump in next time with the curriculum article. What a feast we will enjoy.

It’s just hitting me as I type these words, the irony of it all. I even used an actual picture from my real life last Thanksgiving in this article to drive home the point of Charlotte’s proposed feast and here I am finishing just in time for Thanksgiving. As disappointed as I’ve been that it’s taken me this long to finish a summer series, I have to smile when I think of writing about Charlotte’s curriculum feast the week of Thanksgiving. God’s timing is so sweet; I can almost see Him winking at me.

Join me next time for our final article as we cover principles 11-15. Be sure to subscribe to my free Substack so you’ll be notified of new articles. (pssst…did you know you can become a paid subscriber and support the work I do? And coming soon, you’ll also get cool bonus content as a thank you for your support?)

You can also follow along on my podcast, Homeschooling Outside the Box, and my Instagram.

If you enjoyed this article, please like, subscribe, and share. It helps get the word out and encourage other moms just like you and I would sure appreciate it :).

Till next time, keep living outside the box.